Markets may seem chaotic now, but we don’t see it that way. Our view is that we are witnessing a major structural change, one with a magnitude that might be observed once in 100 years. This type of structural change puts money in motion and provides an investment opportunity to get ahead of that money, not merely follow it.

But this requires a conceptual framework to have this understanding. Let me explain.

For the past few generations, we have been living in a post-Bretton Woods financial era. If you ever took an economics course, you likely heard about Bretton Woods, NH, where in 1944 allied nations came together to decide on a post-war order designed to rebuild global economies. Since the U.S. would clearly emerge as the strongest economy, the U.S. dollar (USD) should then be as strong, designating it as the reserve currency and fully convertible into gold. This meant other currencies would be weaker, enabling these countries to rebuild their export base, manufacturing and economies much more easily.

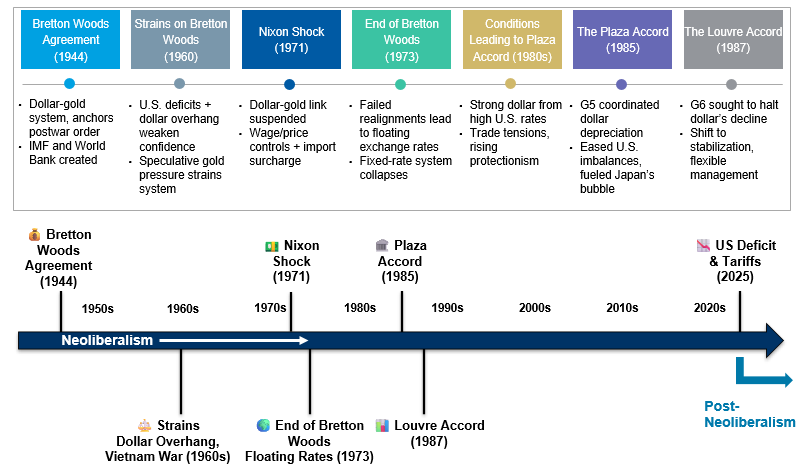

The agreement was necessary and sound, but with one major drawback: It meant the U.S. would likely run a deficit, something that would need to be handled competently in the post-Bretton Woods period. In fact, the management of this deficit has been the crux of major geo-economic events since the end of World War II (Display 1).

By the late 1960s the U.S. was embroiled in the Vietnam War and faced with a rising deficit. Many other countries saw this as an opportunity to convert their USD into gold, such that U.S. gold reserves dropped precipitously. In the early 1970s U.S. President Nixon considered this a serious threat to national security and terminated the Bretton Woods agreement and the easy conversions. This was a major economic event that ushered in fiat money (i.e., money created and backed by a government) and became know as the Bretton Woods II era.

But this only addressed the U.S. deficit temporarily. By the early 1980s the U.S. found itself once again with a growing deficit and called a meeting with large-economy trading partners at the Plaza Hotel in New York City. Another agreement was then reached in 1985 to use foreign exchange intervention to reduce the value of the USD and strengthen foreign currencies. It was known as the Plaza Accord.

The Plaza Accord created debilitating economic volatility across financial markets, and was ultimately viewed as a major policy failure. Things became so chaotic that a mere two years later nations met again, this time at the Louvre in Paris, to dismantle the Plaza Accord and vowing never again to use major currency interventions to address the U.S. deficit. The Louvre Accord was brought to life in 1987.

Regardless of the new approach, the U.S. deficit remained an endemic risk to post-Bretton Woods policy. In 2001 China joined the World Trade Organization and deficits continued to grow. Beyond that, the demographic challenges of an aging population significantly worsened the trajectory of the deficit.

So how can deficit risk be addressed if one chooses not to use currency policy?

Tariffs.

The use of tariffs meant a return to the pre-Bretton Woods period and how countries interacted with each other for hundreds of years prior. U.S. tariff policy was introduced by President Trump in his first term, continued by President Biden and then reaccelerated in Trump’s second term. In fact, subsequent presidents are likely to keep tariffs in place. Why? Because the U.S. deficit will remain a problem for the next few generations as the Baby Boomers age, with the larger Millennial cohort soon thereafter. The U.S. is not alone in this demographic challenge; it’s a global phenomenon.

Admittedly, this is a highly rudimentary summary of the past 80 years. And to be sure, there are many ways to address a deficit beyond just tariffs, with responsible spending by governments at the top of the list. But least painful for elected leaders are tariffs, which is why we think they remain the default choice. After all, there are hundreds of years of economic history prior to Bretton Woods to support this.

A Conceptual Framework to Invest Ahead of the Money

In addition to tariffs (and responsible spending), there is another way to address deficits, namely economic growth policies. This is where we find ourselves today, with country leaders understanding that the construct of economic trade and growth will change in the future. It’s a race that has already started and like any race, one wants to have a great pole position at the start. This is why both foreign and trade policies are currently in flux.

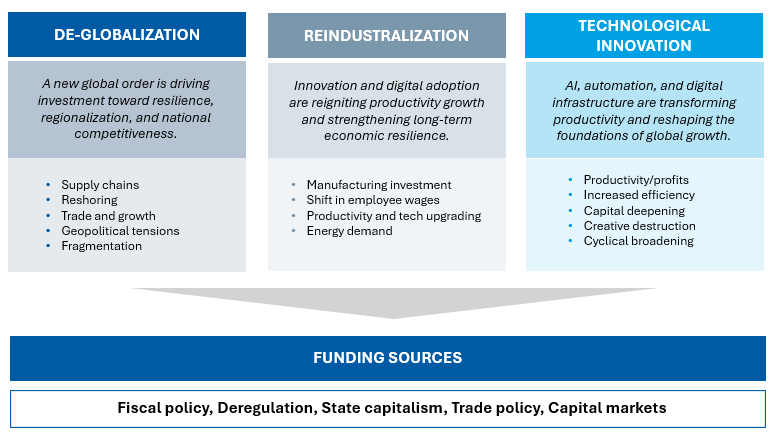

As you can see in Display 2, we have built a conceptual framework for what we believe comes next, one that breaks down into four investable themes:

- Deglobalization. The world has not yet deglobalized, but plans to over the next ten years. Money is being spent now to ensure early pole position in the race for future growth. This creates geopolitical tension and market fragmentation.

- Reindustrialization. If a country is going to deglobalize then it needs to manufacture its own products. This creates opportunities across capital expenditure and manufacturing investment.

- Technological Innovation. As leading economies reindustrialize they will want to use advanced manufacturing. This leads to higher productivity, but also ushers in creative destruction. Not all companies will be able to leverage technology as well as others, creating investment opportunities we can identify as using technology to unlock economic value.

- Funding. This structural change will cost a lot of money and will need to be funded. Equity, debt and private market capital will certainly be used. But governments will fund it too through fiscal policy, tax policy and deregulation, all designed to incentivize private market companies to make this change. We call this State Capitalism. Understand that this is a supply-side initiative and can’t be funded by governments directly because it will worsen their deficit positions. The more productive private sector will have to do the heavy lifting.

Finding Clarity Out of Chaos:

Using Our Conceptual Framework to Identify Investment Opportunities

If we believe that policy is going to support these structural changes then we can use large language models to understand global policies and identify sectors and industries that may benefit most. We can do the same with deregulation.

There are many ways we leverage this conceptual framework to inform our decision making through investment selection of managers, ETFs and baskets of equities. Both passive and active investments have a role to play. Similarly, we use this to bolster our understanding of growth and inflation that impacts our management of fixed income assets. We find ways to use both active and passive management from our investment selection and quantitative research to optimize portfolio construction and position sizing. This is what we are embedding into our strategies.

Structural changes of this magnitude will put money in motion, and our strategy is to get ahead of the money, not follow it.

Featured Insights